More than 200 years ago, a 22-year-old French woman cut off her hair, disguised herself as a man, stowed away on a ship, and became the first woman to document a circumnavigation of the world.

But her story was almost lost to the world, thanks to male editors and censorship.

And it might have stayed hidden forever, were it not for a modern push to bring women’s perspectives to the fore.

Professor Clare Wright, a La Trobe University professor of history and author, says there are many invisible women of history, and that going back to the archives with a sense of curiosity could help uncover previously unheard perspectives.

And writing women back into history is about setting the record straight.

“Women were there … they were history makers, they participated in events, they agitated, they invented, they explored, they colonised, they resisted colonisation.

“Basically any historical activity you want to document, women were there doing the same thing.”

The stowaway

It was 1817 when Rose de Freycinet, disguised as a man, boarded her French naval husband’s ship, the Uranie, and hid in a special cabin he had prepared for her.

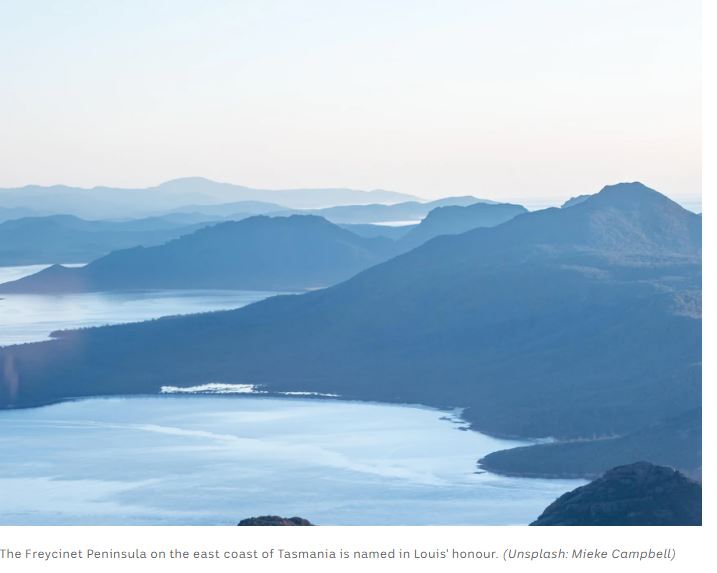

Her husband, Louis de Freycinet — the namesake of the picturesque Freycinet Peninsula on the east coast of Tasmania — had become the first person to publish a complete map of Australia’s coastline as a sub-lieutenant of French naturalist Nicolas Baudin.

Six years later, the French government awarded Louis his own scientific expedition to return to the South Seas, but this time he was newly married and in love.

His was a small wooden ship with 120 men on board and having a woman embark was strictly illegal. So he pretended he needed an extra officer’s cabin and made a few refurbishments.

“What he was doing was secretly supplying a place where Rose could have some privacy,” author and historian Suzanne Falkiner tells ABC RN’s Late Night Live.

Making her invisible

Being invisible onboard the Uranie was critical not only for Rose’s safety — but also Louis’ reputation.

“Rose had to stay hidden until they were out of territorial waters, and then there was some danger that when they landed in French territory, the officials there would arrest her,” Ms Falkiner, the author of Rose: The extraordinary journey of Rose de Freycinet, says.

“The King said something like ‘well, perhaps the less said, the better'”, Ms Falkiner says.

Rose’s embarkation remained a secret on the Uranie until Louis invited his officers to tea and told them she was onboard.

Ms Falkiner says the officer’s reactions were mixed but that some weren’t happy. Women were thought to bring bad luck to ships, and the Uranie’s navigator Gabriel Lafond, who wrote about the voyage more than two decades later, says she was an “apple of discord” among the crew and officers.

So, while she spent two and a half years onboard the Uranie, Rose rarely appeared on deck. Instead, she kept to her cabin, teaching herself to play guitar, learning English and doing needlework.

She was also an intellectual companion for Louis and supported him by researching the places they were destined to visit.

Rose’s presence was largely unacknowledged by those onboard. “Everybody had to pretend that Rose wasn’t there — because officially she wasn’t there,” Ms Falkiner says.

This included the ship’s artists Jacques Arago and Alphonse Pellion, who were tasked with visually documenting the expedition.

“Quite often they did two versions of paintings, a private version where Rose was visible and then another one, which was censored.

“There are actual drafts where there’s a line drawn through the figure of Rose, so the engraver could leave her out.”

Not the full story

Although she was cut from the official records of the expedition, Rose kept a journal documenting the voyage.

The journals were addressed to her friend Caroline de Nanteuil back in France. Ms Falkiner says there’s a lightheartedness in many of Rose’s observations. They included banter about foreign fashion, social norms and the various dignitaries she encountered along the way.

The original handwritten version gives a women’s perspective of a time dominated by male voices.

But Ms Falkiner says the published version doesn’t tell the full story. “They [the journal entries] passed through the hands of several male editors who cut out things they thought might be a bit disreputable.”

For example, names of prominent figures were redacted, while other indiscreet observations of dignitaries were ‘toned down’ including those of the French consul in Tenerife and Baron de Richemont and his wife on Île Bourbon.

Specific details about Louis’ poor health and inability to work for portions of the trip, including his nervous colic and treatment with opium, were also not published.

Losing the Uranie

Rose was the first woman to document a circumnavigation of the globe, but she almost didn’t make it back to France.

In early 1820, after rounding Cape Horn, the southernmost headland of Chile’s Tierra del Fuego archipelago, the Uranie was damaged in a storm.

Louis decided to make for the Falkland Islands where the boat could be repaired, and their supplies restocked from the wild cattle and pigs on the island.

Though they reached the Falklands and navigated into French Bay as planned, the Uranie would never make it back to France.

“There was a subterranean rock that wasn’t marked on their charts, and they ran straight into it,” Ms Falkiner says.

Louis managed to run the ship aground on the beach. Rose’s journal details how he instructed everyone to remain on board to save essential items, despite enormous waves lifting the vessel up and dropping it onto the sand.

He managed to salvage many of the scientific papers and natural history specimens onboard, as well as the guns and barrels of brandy.

He also ensured no lives were lost, though the struggle to survive on the island had only just begun.

Everyone had to live in makeshift tents, made of old boat sails, and endure freezing temperatures, living off the land and rationing their dwindling supplies.

“The hardship and anxiety made Louis very ill,” Ms Falkiner says.

Rose’s journal reveals her own anxiety about Louis’ poor health. “She wondered what would happen if he died,” Ms Falkiner says.

Personal tragedy aside, Rose was aware that a mutiny among the 120-strong crew would have put her in a very vulnerable position.

Fortunately Louis survived. And after two long months, the castaways were rescued by the crew of an American whaling boat.

They were all returned to France in November 1820. However for Louis and Rose, it wasn’t a triumphant return.

Louis faced a court martial for losing his ship. Eventually he was exonerated of any wrongdoing.

“He was handed back his sword. They said he handled it the best way he could and hadn’t lost anyone,” Ms Falkiner says.

In the official court documents, Rose isn’t mentioned at all. “They just pretended it hadn’t happened.”

Writing women back into history

Professor Wright says writing women back into history is about restorative justice.

“Women have been written out of events for political means, and it’s part of a political moment to put them back in.”

She says historically it didn’t take much to silence women’s voices: even if they were recorded, they were often ignored, while mentions of women in other sources are also overlooked.

For example, as part of her research into the women and children of the Eureka Stockade, Professor Wright discovered a woman had been killed during the rebellion trying to protect her husband. Yet this hadn’t made it to any of the subsequent histories.

“It wasn’t buried in an obscure source; it was right smack bang in the middle of a diary that someone in Ballarat had written at the time and that many historians had used before me.”

“All of the monuments in Ballarat, all of the lists of the dead, all of the statues of the brave men who fell at Eureka and who had then become part of folklore and legends, had left out the fact that there was at least one woman killed.”

Professor Wright says the issue is often that no one had asked the question: “Were women there, and if so, what were they doing?”

She believes the need to write women back into history is evident looking at our statues.

“In Australia, only three per cent of our statues are of real historical women,” she says.

“We have more statues of animals.”

And she says there is a crucial reason why the achievements of women like Rose de Freycinet and others like her should be brought to light. “Women are empowered by knowing their own history. If they understand the things that they were capable of doing in the past, it gives women more control and agency over their own actions in the present and potentially their activities in the future.”

ABC RN / By Erin Stutchbury and Catherine Zengerer for Late Night Live

Posted Wed 4 May 2022 at 5:00amWednesday 4 May 2022 at 5:00am, updated Tue 10 May 2022 at 9:31am